Asian Hip-Hop Artists show solidarity to the same struggle of oppressive rule in the region

by May Yu

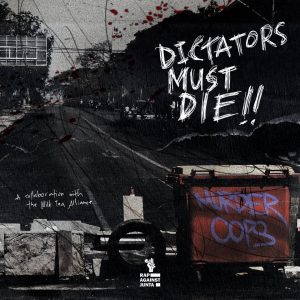

“The military in Myanmar and Papua are the same /Never satisfied, attacking residents and not loving their lives/ Can’t sleep at night. The deceased will come” are the rap lyrics in Bahasa Indonesia by Rand Slam which open a fiery hip-hop track,”Dictators Must Die”.

Indonesian hip-hop artist Rand Slam’s lyrics are a reference to state-sponsored violence committed by Myanmar and Papua militaries against innocent civilians. The track is by the Rap Against Junta, a Myanmar-based hip-hop collective, through a collaboration of 12 hip hop artists from six countries that are members of the Milk Tea Alliance.

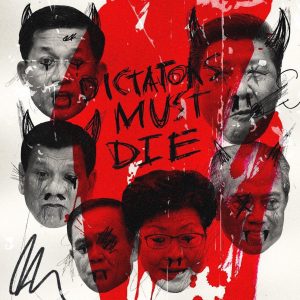

This hip-hop track is a collaboration of rappers from Asian countries that are home to fragile democracies and government incompetence which has oppressed basic rights and fundamental freedoms, including those tied to expression. Hip-hop artists, dancers, sound engineers and editors from Myanmar,Thailand, Indonesia, Hong Kong, India and Taiwan have long expressed their frustrations and anger against their countries’ corrupt politicians, failed and outdated political systems and violations of human rights. They have also called for the downfall of their respective regional dictators.

The track was launched on June 30 this year, five months after the coup in Myanmar. It now has more than 4,500 views, and the comment section showed sentiments expressing solidarity and support by the netizens from the Milk Tea Alliance nations. Myanmar citizens wrote messages of gratitude who say they are more motivated to fight against any form of dictatorships together with other countries who share their struggle.

In the track, a Thai artist named Hockhacker, rapped the lyrics: “You fight with the wrong generation. We fight for a real revolution.” This echoes Myanmar protests’ chants where people say this is a generation different from 1988, when Myanmar saw one of the biggest protests in modern history against the military rule, resulting in thousands of deaths as the soldiers shot the protesters. The military’s former tricks and tactics will not work on the people in 2021 says the people.

Hockhacker is a member of the coalition of rapper activists in Thailand known as “Rap Against Dictatorship”, a group which uses verses of defiance to criticize the government in a 2018-debut called Prathet Ku Mee (What My Country has..). The song went viral with over one hundred million views. Having participated in youth-led demonstrations calling for reform of the political system, including the role of the monarchy and the military last year, Hockhapper expressed sympathy to Myanmar’s struggle for freedom and reforms.He immediately said yes to the Milk Tea Alliance project and stated,“I want to be in the same song as the artists who dare to fight the power of the state. Many countries face a more serious situation than Thailand. Especially Myanmar, they faced very hard times. What I can help with is this show of strength”.

However, political music has clearly struck a nerve with the leaders in the region. Hip-Hop artists and rappers who defy the existing political system and demand for reforms continue to face harassment and threats of arrests and detention from the authorities. Thai rapper Hockhacker’s home was raided, and he was charged with six criminal counts that included inciting rebellion,(sedition), for his involvement in one of the biggest protests that Thailand had last year. This is not unusual in the region which has been cursed with fragile democracy and limits on exercising one’s political rights. Kea Sokun, a 23-year-old rap artist of Cambodia, was accused of inciting criminal activity for his two songs posted on his YouTube page under Cambodia’s criminal code. He was arrested in September 2020, and just recently released after spending a year in prison for exercising his right to freedom of expression.

In Myanmar, since the ousting of the elected government in February’s coup, hip-hop artists who have been vocal against the junta have been forced into hiding. Many have been forced to change their names or hide their identities, or digitally alter their voices to produce political rap in order to avoid retaliation from the junta.

A former informal host of Hip-Hop shows, and a key member of the Rap Against Junta, Ko Aye Win, said in an interview that in the early days of protesting in February in Myanmar, one could organize street protest performances openly that included all four different elements of Hip-Hop: graffiti art, breakdance, DJ and rap. Yet, things have changed with increasing indiscriminate violence committed by the junta. He added, “Many protest songs to motivate the public were produced those days. But now, things have changed. Many of my rapper friends had gone into hiding, and had joined the People Defense Forces (PDF) in liberated areas, some were arrested and some were on the wanted list. We have this platform, Rap Against Junta, to support rappers who want to produce protest art without using their real names, and without having to promote it on their personal channels. This platform is to encourage the artists to keep on participating in the revolution in any way they can as everyone in the country is playing a different role.”

Another rapper in Myanmar who goes by the name of 882021, and who is involved in the Rap Against Junta collective hides his identity for fear of retaliation from the junta. He had to come up with a new name for safety concerns, and produced his two rap songs, Lee Coup and Lee 199 under Rap Against Junta for his safety. His name, 882021, is the combination of two numbers of the years (1988 and 2021) that represent some of the biggest protests against military rule in Myanmar modern history. In an interview, he said, “Rap has a long political history that is bold and rebellious in standing against injustice and to fight for freedom. Rap has indescribable energy, and the messages are direct and easy to communicate with the audience.”

He added that artists need to keep on producing protest art and music to keep the people’s spirits high. “However, he added, “I’d recommend artists to stay anonymous. If the artists boldly take a stance, the military goes out for them. It is scary to know that you can get arrested or killed just for expressing yourself.”

If the military continues to hold the power and if Myanmar returns to military rule before the country’s experiment with the transition to democracy, there will be no true art. He said he is afraid of turning back to the not so distant past in Myanmar, “The essence of art is expression. If the expression is under controlled, and censored, there will never be a true form of art.” 882021 is determined to continue defying the junta through his artistic expression, bold and fierce, and to communicate to an international audience to bring awareness of what is happening in the country.

Ko Aye Win shares the same sentiment that more people in the international community can be informed through this type of collaboration from the countries that are going through this period of oppression. He said, “Through this collaboration I want the world to show us solidarity for what we are fighting for. This [Dealing with oppressive political system] is like a disease, and a big problem in Asia. But we are not given much attention. We want to be united and our aim is world peace and the downfall of dictators.”

In the chorus, a fearless angelic voice of Cori Rey from Myanmar sang “No way to turn back. No Way to give up. No way to lose as we know this is the end. Nothing can stop us now, we will fight till the end.”