Seni Rupa Penyadaran (Art for Conscientization)

by Siti Adiyati Subangun

Photo by Siti Adiyati Subangun, taken from the Kompas clipping.

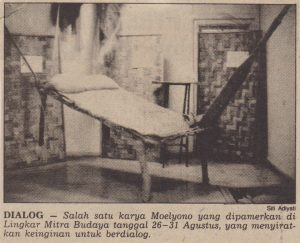

There were two bamboo divans topped with plaited mats, dingy pillows, and blankets made out of fishnets that were suspended up to the corner walls. Around it, there were boat paddles, oil lanterns made out of used tin cans, and woven bamboo wall panels. This installation was set in the gallery space of Lingkar Mitra Budaya, located at Tanjung St., Central Jakarta, from the 20th to the 31st of August, 1988.

The space is far from a cheerful setting as it was dimly lit. It tend to feel gloomy and impoverished as suggested by the interior set up. Here and there, woven bamboo panel walls and humble frames are used to exhibit drawings of children from an elementary school near a beach, in a remote area.

With multiple types of paper that they could get, pencils, crayons or markers brought from the city, they drew and wrote stories about their everyday experiences. People seemed to be surprised when faced with such a happening. For some, the event’s title, Pameran Seni Rupa Dialogis Transformatif (Dialogically Transformative Art Exhibition), adds to its oddness. Generally speaking, from an art world perspective, it is rather hard to see the drawings as art as they don’t reflect any form of mastery, craft, or aesthetic beauty. If we look further to the ways in which they are dealing with their (chosen) subject matter, we’d find that they seem to have not surpassed amateur levels.

(Being) poor is beautiful

This was Moelyono’s doing. The art-school graduate is known to have been veering away from the typical pathways of art-making, yet, he keeps on pushing further various ideas, processes in search of a more meaningful life. It seems like, for him, art(s practice) is much like the water from a vase irrigating a gutter that has long dried.

Every year since around 1982, Pak Moel —a nickname from his students— would make some sort of an “action” in different villages or with particular societies. These “actions” have almost always involved the people living in the area.

For example, what happened when he used the rays of sun that came through a cave in Lowo Sripit, Trenggalek; or when he made an enormous cikrak (bamboo-based garbage bin) to cover the hilltop popularly known as the incarnation of the legendary figure Joko Budeg; or the time he spread perfume-like fragrances in the poultry area of Beringhardjo Market, Yogyakarta as an act of anticipating the bad smell of chicken shit; or a rendezvous of actions when he lived in Waung Village with its people. He’d done all that prior to his arrival to these rural beaches, Brumbun and Nggerangan, which are the places that were depicted in the exhibition with such an ominous title.

Almost all of the locations of his actions are in East Java and they are truly impoverished and problematic. Why? Moelyono the drawing teacher himself is from Tulungagung [one of the riverside cities of East Java, trans.]. All of his compassion and humanity “called” him out and drove him to be a part of recurring cycles of societal issues. Therefore, the kind of art that he had learnt in the academy could not fulfil his soul nor his conscience when faced with the bitter reality of the environment that he is living in. Art can no longer remain extraneous, art is a form of conscientization, art shall become the “beauty” of their lives. With this crystal clear stance, the artist Moelyono is truly enacting a dialogue.

Can “art” approach really take him into the actual problems? Will drawing, storytelling and playfulness, allow Moelyono to empathize with the conundrum of these people?

Dialogue

Nowadays, (it seems that) children draw spontaneously, be it on the sand or on paper. Before Pak Moel came, they may not even know about such activities. Now, they can draw a piece of rice with small dots on top of their plates. Afterwards, they can laugh because rice for them is rare, expensive, and it would almost be like a dream to have met this Sri Goddess’ meal. Depiction of everyday life, the mundane, such as household appliances, people fishing with neet, adults’ fighting for water hose, what one wants to be when one grew up, working as a labour, dreams of becoming a boar, butterfly, frog, snake, fish, shrimp, and so on, really do reflect alienation from external world.

Government’s malaria or dengue campaign that was once broadcasted on the only radio channel in the village of 34 families (Brumbun) and 14 families (Nggerangan) was revisited in great detail. How everyone had to wear a necklace with barus camphor as its pendant so that mosquitos wouldn’t want to come and bite one’s body? The form of this barus camphor pendant, rounded rectangle, is found in so many drawings, some even appeared with texts as if it is more convincing.

Also, in almost every field of their drawings, we’d find text accompanying drawings. Maybe, just maybe, they are not that sure that drawing is meaningful enough for people to understand, unlike other societies in which symbols are the basis of their writings. Therefore we can clearly see that they are inclined to be more understood, hence the use of these verbal expressions that are straightforward and honest.

Therefore, these forms that happened because of lines that were dragged with hiccups and shuddering fingers, which clearly do not perform a mastery of object depiction. Instead, unravels their courage in expressing their thoughts as well as their search for a better understanding of themselves, the positionalities. Surely none of this changes the fact that impoverishment is still happening, but, the act of drawing such a situation offers a chance to shift the perspectives on life and living. Maybe, this is the situation that the guy behind this project meant as a dialogue, a setting in which players meet with other players, and they are both standing on the same stage. None are exploiting one another.

Where do we draw the line for (what is) art and (what is) not if societal problems are central to the idea, the thinking, the subject matter, and the expression, all at the same time? For the drawing teacher Pak Moel, art is the attitude of living and he has always positioned himself as the lower class citizens. Art is a tool to dissect social injustices and imbalances, to him, as it never could remain still in the “high culture” scene. If so, could transformation happen as the exhibition introduction suggested?